Griseofulvin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gris-peg, Grifulvin V, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682295 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Highly variable (25 to 70%) |

| Metabolism | Liver (demethylation and glucuronidation) |

| Elimination half-life | 9–21 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.335 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

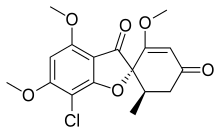

| Formula | C17H17ClO6 |

| Molar mass | 352.77 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Griseofulvin is an antifungal medication used to treat a number of types of dermatophytoses (ringworm).[1] This includes fungal infections of the nails and scalp, as well as the skin when antifungal creams have not worked.[2] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include allergic reactions, nausea, diarrhea, headache, trouble sleeping, and feeling tired.[1] It is not recommended in people with liver failure or porphyria.[1] Use during or in the months before pregnancy may result in harm to the baby.[1][2] Griseofulvin works by interfering with fungal mitosis.[1]

Griseofulvin was discovered in 1939 from the soil fungus Penicillium griseofulvum.[3][4][5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6]

Medical uses

[edit]Griseofulvin is used orally only for dermatophytosis. It is ineffective topically. It is reserved for cases in which topical treatment with creams is ineffective.[7]

Terbinafine given for 2 to 4 weeks is at least as effective as griseofulvin given for 6 to 8 weeks for treatment of Trichophyton scalp infections. However, griseofulvin is more effective than terbinafine for treatment of Microsporum scalp infections.[8][9]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]The drug binds to tubulin, interfering with microtubule function, thus inhibiting mitosis. It binds to keratin in keratin precursor cells and makes them resistant to fungal infections. The drug reaches its site of action only when hair or skin is replaced by the keratin-griseofulvin complex. Griseofulvin then enters the dermatophyte through energy-dependent transport processes and binds to fungal microtubules. This alters the processing for mitosis and also underlying information for deposition of fungal cell walls.[citation needed]

Biosynthesis

[edit]It is produced industrially by fermenting the fungus Penicillium griseofulvum.[10][11][12]

The first step in the biosynthesis of griseofulvin by P. griseofulvin is the synthesis of the 14-carbon poly-β-keto chain by a type I iterative polyketide synthase (PKS) via iterative addition of 6 malonyl-CoA to an acyl-CoA starter unit. The 14-carbon poly-β-keto chain undergoes cyclization/aromatization, using cyclase/aromatase, respectively, through a Claisen and aldol condensation to form the benzophenone intermediate. The benzophenone intermediate is then methylated via S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) twice to yield griseophenone C. The griseophenone C is then halogenated at the activated site ortho to the phenol group on the left aromatic ring to form griseophenone B. The halogenated species then undergoes a single phenolic oxidation in both rings forming the two oxygen diradical species. The right oxygen radical shifts alpha to the carbonyl via resonance allowing for a stereospecific radical coupling by the oxygen radical on the left ring forming a tetrahydrofuranone species.[13] The newly formed grisan skeleton with a spiro center is then O-methylated by SAM to generate dehydrogriseofulvin. Ultimately, a stereoselective reduction of the olefin on dehydrogriseofulvin by NADPH affords griseofulvin.[14][15]

Toxicology

[edit]Mice

[edit]Griseofulvin is found to alter the bile metabolism of mice by Yokoo et al. 1979. The same team went on to find a similar effect on mice by a chemically unrelated substance, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine, in Yokoo et al. 1982 and Tsunoo et al. 1987.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Griseofulvin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 149. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ Block SS (2001). Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 631. ISBN 9780683307405. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ Ash M, Ash I (2004). Handbook of Preservatives. Synapse Info Resources. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-890595-66-1. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013.

- ^ Beekman AM, Barrow RA (2014). "Fungal metabolites as pharmaceuticals". Australian Journal of Chemistry. 67 (6): 827–843. doi:10.1071/ch13639.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Mutschler E, Schäfer-Korting M (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 838. ISBN 3-8047-1763-2.

- ^ Fleece D, Gaughan JP, Aronoff SC (November 2004). "Griseofulvin versus terbinafine in the treatment of tinea capitis: a meta-analysis of randomized, clinical trials". Pediatrics. 114 (5): 1312–1315. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0428. PMID 15520113. S2CID 34976866.

- ^ Chen X, Jiang X, Yang M, González U, Lin X, Hua X, et al. (May 2016). "Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD004685. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004685.pub3. PMC 8691867. PMID 27169520.

- ^ Oxford AE, Raistrick H, Simonart P (February 1939). "Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms: Griseofulvin, C(17)H(17)O(6)Cl, a metabolic product of Penicillium griseo-fulvum Dierckx". The Biochemical Journal. 33 (2): 240–248. doi:10.1042/bj0330240. PMC 1264363. PMID 16746904.

- ^ Grove JF, Ismay D, Macmillan J, Mulholland TP, Rogers MA (1951). "The structure of griseofulvin". Chemistry and Industry. 11. London: 219–220.

- ^ Grove JF, MacMillan J, Mulholland TP, Rogers MA (1952). "762. Griseofulvin. Part IV. Structure". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 3977. doi:10.1039/JR9520003977.

- ^ Birch A (1953). "Studies in relation to biosynthesis I. Some possible routes to derivatives of orcinol and phloroglucinol". Australian Journal of Chemistry. 6 (4): 360. doi:10.1071/ch9530360.

- ^ Dewick PM (2009). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach (3rd ed.). UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-0-471-97478-9.

- ^ Harris CM, Roberson JS, Harris TM (August 1976). "Biosynthesis of griseofulvin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (17): 5380–5386. doi:10.1021/ja00433a053. PMID 956563.

- ^ Knasmüller S, Parzefall W, Helma C, Kassie F, Ecker S, Schulte-Hermann R (September 1997). "Toxic effects of griseofulvin: disease models, mechanisms, and risk assessment". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 27 (5). Taylor & Francis: 495–537. doi:10.3109/10408449709078444. PMID 9347226.

- Pages using the JsonConfig extension

- Antifungals

- Aromatic ketones

- Benzofuran ethers at the benzene ring

- Chloroarenes

- Cyclohexenes

- Disulfiram-like drugs

- Halogen-containing natural products

- IARC Group 2B carcinogens

- Mutagens

- Resorcinol ethers

- Spiro compounds

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- Terpenes and terpenoids