Bing Crosby

Bing Crosby | |

|---|---|

Crosby c. 1940 | |

| Born | Harry Lillis Crosby Jr. May 3, 1903 Tacoma, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | October 14, 1977 (aged 74) Alcobendas, Spain |

| Resting place | Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Gonzaga University |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1923–1977 |

| Works | |

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Relatives |

|

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Labels | |

| Website | bingcrosby |

| Signature | |

| |

Harry Lillis "Bing" Crosby Jr. (May 3, 1903 – October 14, 1977) was an American singer and actor. The first multimedia star, he was one of the most popular and influential musical artists of the 20th century worldwide.[1] Crosby was a leader in record sales, network radio ratings, and motion picture grosses from 1926 to 1977. He was one of the first global cultural icons.[2] Crosby made over 70 feature films and recorded more than 1,600 songs.[3][4][5]

Crosby's early career coincided with recording innovations that allowed him to develop an intimate singing style that influenced many male singers who followed, such as Frank Sinatra,[6] Perry Como, Dean Martin, Dick Haymes, Elvis Presley, and John Lennon.[7] Yank magazine said that Crosby was "the person who had done the most for the morale of overseas servicemen" during World War II.[8] In 1948, American polls declared him the "most admired man alive", ahead of Jackie Robinson and Pope Pius XII.[3]: 6 [9] In 1948, Music Digest estimated that Crosby's recordings filled more than half of the 80,000 weekly hours allocated to recorded radio music in America.[9]

Crosby won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in Going My Way (1944) and was nominated for its sequel, The Bells of St. Mary's (1945), opposite Ingrid Bergman, becoming the first of six actors to be nominated twice for playing the same character. Crosby was the number one box office attraction for five consecutive years from 1944 to 1948.[10] At his screen apex in 1946, Crosby starred in three of the year's five highest-grossing films: The Bells of St. Mary's, Blue Skies, and Road to Utopia.[10] In 1963, he received the first Grammy Global Achievement Award.[11] Crosby is one of 33 people to have three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame,[12] in the categories of motion pictures, radio, and audio recording.[13] He was also known for his collaborations with his friend Bob Hope, starring in the Road to ... films from 1940 to 1962.

Crosby influenced the development of the post–World War II recording industry. After seeing a demonstration of a German broadcast quality reel-to-reel tape recorder brought to the United States by John T. Mullin, Crosby invested $50,000 in the California electronics company Ampex to build copies. He then persuaded ABC to allow him to tape his shows and became the first performer to prerecord his radio shows and master his commercial recordings onto magnetic tape. Crosby has been associated with the Christmas season since he starred in Irving Berlin's musical film Holiday Inn and also sang "White Christmas" in the film of the same name. Through audio recordings, Crosby produced his radio programs with the same directorial tools and craftsmanship (editing, retaking, rehearsal, time shifting) used in motion picture production, a practice that became the industry standard.[14] In addition to his work with early audio tape recording, Crosby helped finance the development of videotape, bought television stations, bred racehorses, and co-owned the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team, during which time the team won two World Series (1960 and 1971).

Early life

[edit]

Crosby was born on May 3, 1903,[15][16] in Tacoma, Washington, in a house his father built at 1112 North J Street. Three years later, his family moved to Spokane in Eastern Washington state, where Crosby was raised.[17] In 1913, his father built a house at 508 E. Sharp Avenue.[18] The house stands on the campus of Crosby's alma mater, Gonzaga University, as a museum housing over 200 artifacts from his life and career, including his Oscar.[19][20]

Crosby was the fourth of seven children: brothers Laurence Earl "Larry" (1895–1975), Everett Nathaniel (1896–1966), Edward John "Ted" (1900–1973), and George Robert "Bob" (1913–1993); and two sisters, Catherine Cordelia (1904–1974) and Mary Rose (1906–1990). His parents were Harry Lillis Crosby[21] (1870–1950), a bookkeeper, and Catherine Helen "Kate" (née Harrigan; 1873–1964). His mother was a second-generation Irish-American.[22][3] His father was of Scottish and English descent; an ancestor, Simon Crosby, emigrated from the Kingdom of England to New England in the 1630s during the Puritan migration to New England.[23][24] Through another line, also on his father's side, Crosby is descended from Mayflower passenger William Brewster (c. 1567 – 1644).[3]: 24 [25]

In 1917, Crosby took a summer job as property boy at Spokane's Auditorium, where he witnessed some of the acts of the day, including Al Jolson, who held Crosby spellbound with ad-libbing and parodies of Hawaiian songs. Crosby later described Jolson's delivery as "electric".[26]

Crosby graduated from Gonzaga High School in 1920 and enrolled at Gonzaga University. He attended Gonzaga for three years but did not earn a degree.[27] As a freshman, Crosby played on the university's baseball team.[28] The university granted him an honorary doctorate in 1937.[29] Gonzaga University houses a large collection of photographs, correspondence, and other material related to Crosby.[30]

On November 8, 1937, after Lux Radio Theatre's adaptation of She Loves Me Not, Joan Blondell asked Crosby how he got his nickname:

Crosby: "Well, I'll tell you, back in the knee-britches day, when I was a wee little tyke, a mere broth of a lad, as we say in Spokane, I used to totter around the streets, with a gun on each hip, my favorite after school pastime was a game known as "Cops and Robbers", I didn't care which side I was on, when a cop or robber came into view, I would haul out my trusty six-shooters, made of wood, and loudly exclaim bing! bing!, as my luckless victim fell clutching his side, I would shout bing! bing!, and I would let him have it again, and then as his friends came to his rescue, shooting as they came, I would shout bing! bing! bing! bing! bing! bing! bing! bing!"

Blondell: "I'm surprised they didn't call you "Killer" Crosby! Now tell me another story, Grandpa!

Crosby: "No, so help me, it's the truth, ask Mister De Mille."

De Mille: "I'll vouch for it, Bing."[31][32]

As it happens, that story was pure whimsy for dramatic effect; the Associated Press had reported as early as February 1932—as would later be confirmed by both Bing himself and his biographer Charles Thompson—that it was in fact a neighbor—Valentine Hobart, circa 1910—who had named him "Bingo from Bingville" after a comic feature in the local paper called The Bingville Bugle which the young Harry liked. In time, Bingo got shortened to Bing.[33][34][35]

Career

[edit]Early years

[edit]In 1923, Crosby was invited to join a new band composed of high-school students a few years younger than himself. Al and Miles Rinker (brothers of singer Mildred Bailey), James Heaton, Claire Pritchard and Robert Pritchard, along with drummer Crosby, formed the Musicaladers,[5] who performed at dances both for high school students and club-goers. The group performed on Spokane radio station KHQ, but disbanded after two years.[3]: 92–97 [36] Crosby and Al Rinker obtained work at the Clemmer Theatre in Spokane (now known as the Bing Crosby Theater).

Crosby was initially a member of a vocal trio called The Three Harmony Aces with Al Rinker accompanying on piano from the pit, to entertain between the films. Crosby and Al continued at the Clemmer Theatre for several months, often with three other men—Wee Georgie Crittenden, Frank McBride, and Lloyd Grinnell—and they were billed The Clemmer Trio or The Clemmer Entertainers depending who performed.[37]

In October 1925, Crosby and Rinker decided to seek fame in California. They traveled to Los Angeles, where Bailey introduced them to her show business contacts. The Fanchon and Marco Time Agency hired them for 13 weeks for the revue The Syncopation Idea starting at the Boulevard Theater in Los Angeles and then on the Loew's circuit. They each earned $75 a week. As minor parts of The Syncopation Idea, Crosby and Rinker started to develop as entertainers. They had a lively style that was popular with college students. After The Syncopation Idea closed, they worked in the Will Morrissey Music Hall Revue. They honed their skills with Morrissey, and when they got a chance to present an independent act, they were spotted by a member of the Paul Whiteman organization.

Whiteman needed something different to break up his musical selections, and Crosby and Rinker filled this requirement. After less than a year in show business, they were attached to one of the biggest names.[37] Hired for $150 a week in 1926, they debuted with Whiteman on December 6 at the Tivoli Theatre in Chicago. Their first recording, in October 1926, was "I've Got the Girl" with Don Clark's Orchestra, but the Columbia-issued record was inadvertently recorded at a slow speed, which increased the singers' pitch when played at 78 rpm. Throughout his career, Crosby often credited Bailey for getting him his first important job in the entertainment business.[38]

The Rhythm Boys

[edit]

Success with Whiteman was followed by disaster when they reached New York. Whiteman considered letting them go. However, the addition of pianist and aspiring songwriter Harry Barris made the difference, and The Rhythm Boys were born. The additional voice meant they could be heard more easily in large New York theaters. Crosby gained valuable experience on tour for a year with Whiteman and performing and recording with Bix Beiderbecke, Jack Teagarden, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Eddie Lang, and Hoagy Carmichael. Crosby matured as a performer and was in demand as a solo singer.[39]

Crosby became the star attraction of the Rhythm Boys. In 1928, he had his first number one hit, a jazz-influenced rendition of "Ol' Man River". In 1929, the Rhythm Boys appeared in the film King of Jazz with Whiteman, but Crosby's growing dissatisfaction with Whiteman led to the Rhythm Boys leaving his organization. They joined the Gus Arnheim Orchestra, performing nightly in the Coconut Grove of the Ambassador Hotel. Singing with the Arnheim Orchestra, Crosby's solos began to steal the show while the Rhythm Boys' act gradually became redundant. Harry Barris wrote several of Crosby's hits, including "At Your Command", "I Surrender Dear", and "Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams". When Mack Sennett signed Crosby to a solo film contract in 1931, a break with the Rhythm Boys became almost inevitable. Crosby married Dixie Lee in September 1930. After a threat of divorce in March 1931, he applied himself to his career.

Success as a solo singer

[edit]

On September 2, 1931, 15 Minutes with Bing Crosby, his nationwide solo radio debut, began broadcasting.[40] The weekly broadcast made Crosby a hit.[41] Before the end of the year, he signed[clarification needed] with both Brunswick Records and CBS Radio. "Out of Nowhere", "Just One More Chance", "At Your Command", and "I Found a Million Dollar Baby (in a Five and Ten Cent Store)" were among the best-selling songs of 1931.[41]

Ten of the top 50 songs of 1931 included Crosby with others or as a solo act. A "Battle of the Baritones" with singer Russ Columbo proved short-lived, replaced with the slogan "Bing Was King". Crosby played the lead in a series of musical comedy short films for Mack Sennett, signed with Paramount, and starred in his first full-length film, 1932's The Big Broadcast (1932), the first of 55 films in which he received top billing. Crosby would appear in almost 80 pictures. He signed a contract with Jack Kapp's new record company, Decca, in late 1934.

Crosby's first commercial sponsor on radio was Cremo Cigars and his fame spread nationwide. After a long run in New York, Crosby went back to Hollywood to film The Big Broadcast. His appearances, records, and radio work substantially increased his impact. The success of his first film brought Crosby a contract with Paramount, and he began a pattern of making three films a year. Crosby led his radio show for Woodbury Soap for two seasons while his live appearances dwindled. Crosby's records produced hits during the Depression when sales were down. Audio engineer Steve Hoffman stated, "By the way, Bing actually saved the record business in 1934 when he agreed to support Decca founder Jack Kapp's crazy idea of lowering the price of singles from a dollar to 35 cents and getting a royalty for records sold instead of a flat fee. Bing's name and his artistry saved the recording industry. All the other artists signed to Decca after Bing did. Without him, Jack Kapp wouldn't have had a chance in hell of making Decca work and the Great Depression would have wiped out phonograph records for good."[42]

His first son Gary was born in 1933 with twin boys following in 1934. By 1936, Crosby replaced his former boss, Paul Whiteman, as host of the weekly NBC radio program Kraft Music Hall, where he remained for the next decade. "Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day)", with his trademark whistling, became his theme song and signature tune.

Crosby's vocal style helped take popular singing beyond the "belting" associated with Al Jolson and Billy Murray, who had been obligated to reach the back seats in New York theaters without the aid of a microphone. As music critic Henry Pleasants noted in The Great American Popular Singers, something new had entered American music, a style that might be called "singing in American" with conversational ease. This new sound led to the popular epithet crooner.

Crosby admired Louis Armstrong for his musical ability, and the trumpet maestro was a formative influence on Crosby's singing style. When the two met, they became friends. In 1936, Crosby exercised an option in his Paramount contract to regularly star in an out-of-house film. Signing an agreement with Columbia for a single motion picture, Crosby wanted Armstrong to appear in a screen adaptation of The Peacock Feather that eventually became Pennies from Heaven. Crosby asked Harry Cohn, but Cohn had no desire to pay for the flight or to meet Armstrong's "crude, mob-linked but devoted manager, Joe Glaser". Crosby threatened to leave the film and refused to discuss the matter. Cohn gave in; Armstrong's musical scenes and comic dialogue extended his influence to the silver screen, creating more opportunities for him and other African Americans to appear in future films. Crosby also ensured behind the scenes that Armstrong received equal billing with his white co-stars. Armstrong appreciated Crosby's progressive attitudes on race, and often expressed gratitude for the role in later years.[43]

During World War II, Crosby made live appearances before American troops who had been fighting in the European Theater. He learned how to pronounce German from written scripts and read propaganda broadcasts intended for German forces. The nickname "Der Bingle" was common among Crosby's German listeners and came to be used by his English-speaking fans. In a poll of U.S. troops at the close of World War II, Crosby topped the list as the person who had done the most for G.I. morale, ahead of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, General Dwight Eisenhower, and Bob Hope.

The June 18, 1945, issue of Life magazine stated, "America's number one star, Bing Crosby, has won more fans, made more money than any entertainer in history. Today he is a kind of national institution."[44] "In all, 60,000,000 Crosby discs have been marketed since he made his first record in 1931. His biggest best seller is "White Christmas" 2,000,000 impressions of which have been sold in the U.S. and 250,000 in Great Britain."[44] "Nine out of ten singers and bandleaders listen to Crosby's broadcasts each Thursday night and follow his lead. The day after he sings a song over the air—any song—some 50,000 copies of it are sold throughout the U.S. Time and again Crosby has taken some new or unknown ballad, has given it what is known in trade circles as the 'big goose' and made it a hit single-handed and overnight... Precisely what the future holds for Crosby neither his family nor his friends can conjecture. He has achieved greater popularity, made more money, attracted vaster audiences than any other entertainer in history. And his star is still in the ascendant. His contract with Decca runs until 1955. His contract with Paramount runs until 1954. Records which he made ten years ago are selling better than ever before. The nation's appetite for Crosby's voice and personality appears insatiable. To soldiers overseas and to foreigners he has become a kind of symbol of America, of the amiable, humorous citizen of a free land. Crosby, however, seldom bothers to contemplate his future. For one thing, he enjoys hearing himself sing, and if ever a day should dawn when the public wearies of him, he will complacently go right on singing—to himself."[44][45]

White Christmas

[edit]

The biggest hit song of Crosby's career was his recording of Irving Berlin's "White Christmas", which Crosby introduced on a Christmas Day radio broadcast in 1941. A copy of the recording from the radio program is owned by the estate of Bing Crosby and was loaned to CBS Sunday Morning for their December 25, 2011, program. The song appeared in his films Holiday Inn (1942), and—a decade later—in White Christmas (1954). Crosby's record hit the charts on October 3, 1942, and rose to number 1 on October 31, where it stayed for 11 weeks. A holiday perennial, the song was repeatedly re-released by Decca, charting another 16 times. It topped the charts again in 1945 and a third time in January 1947. The song remains the bestselling single of all time.[41] Crosby's recording of "White Christmas" has sold over 50 million copies worldwide. His recording was so popular that Crosby was obliged to re-record it in 1947 using the same musicians and backup singers; the original 1942 master had become damaged due to its frequent use in pressing additional singles. In 1977, after Crosby died, the song was re-released and reached No. 5 in the UK Singles Chart.[46] Crosby was dismissive of his role in the song's success, saying "a jackdaw with a cleft palate could have sung it successfully".[47]

Motion pictures

[edit]

In the wake of a solid decade of headlining mainly smash hit musical comedy films in the 1930s, Crosby starred with Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour in six of the seven Road to musical comedies between 1940 and 1962 (Lamour was replaced with Joan Collins in The Road to Hong Kong and limited to a lengthy cameo), cementing Crosby and Hope as an on-and-off duo, despite never declaring themselves a "team" in the sense that Laurel and Hardy or Martin and Lewis (Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis) were teams. The series consists of Road to Singapore (1940), Road to Zanzibar (1941), Road to Morocco (1942), Road to Utopia (1946), Road to Rio (1947), Road to Bali (1952), and The Road to Hong Kong (1962). When they appeared solo, Crosby and Hope frequently made note of the other in a comically insulting fashion. They performed together countless times on stage, radio, film, and television, and made numerous brief and not so brief appearances together in movies aside from the "Road" pictures, Variety Girl (1947) being an example of lengthy scenes and songs together along with billing.

In the 1949 Disney animated film The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, Crosby provided the narration and song vocals for The Legend of Sleepy Hollow segment. In 1960, he starred in High Time, a collegiate comedy with Fabian Forte and Tuesday Weld that predicted the emerging gap between Crosby and the new younger generation of musicians and actors who had begun their careers after World War II. The following year, Crosby and Hope reunited for one more Road movie, The Road to Hong Kong, which teamed them up with the much younger Joan Collins and Peter Sellers. Collins was used in place of their longtime partner Dorothy Lamour, whom Crosby felt was getting too old for the role, though Hope refused to do the film without her, and she instead made a lengthy and elaborate cameo appearance.[41] Shortly before his death in 1977, Crosby had planned another Road film in which he, Hope, and Lamour search for the Fountain of Youth.

Crosby won an Academy Award for Best Actor for Going My Way in 1944 and was nominated for the 1945 sequel, The Bells of St. Mary's. He received critical acclaim and his third Academy Award nomination for his performance as an alcoholic entertainer in The Country Girl.[48]

Television

[edit]

The Fireside Theater (1950) was his first television production. The series of 26-minute shows was filmed at Hal Roach Studios rather than performed live on the air. The "telefilms" were syndicated to individual television stations. Crosby was a frequent guest on the musical variety shows of the 1950s and 1960s, appearing on various variety shows as well as numerous late-night talk shows and his own highly rated specials. Bob Hope memorably devoted one of his monthly NBC specials to his long intermittent partnership with Crosby titled "On the Road With Bing". Crosby was associated with ABC's The Hollywood Palace as the show's first and most frequent guest host and appeared annually on its Christmas edition with his wife Kathryn and his younger children, and continued after The Hollywood Palace was eventually canceled. In the early 1970s, Crosby made two late appearances on the Flip Wilson Show, singing duets with the comedian. His last TV appearance was a Christmas special, Merrie Olde Christmas, taped in London in September 1977 and aired weeks after his death.[49] It was on this special that Crosby recorded a duet of "The Little Drummer Boy" and "Peace on Earth" with rock musician David Bowie. Their duet was released in 1982 as a single 45 rpm record and reached No. 3 in the UK singles charts.[46] It has since become a staple of holiday radio and the final popular hit of Crosby's career. At the end of the 20th century, TV Guide listed the Crosby-Bowie duet one of the 25 most memorable musical moments of 20th-century television.

Bing Crosby Productions, affiliated with Desilu Studios and later CBS Television Studios, produced a number of television series, including Crosby's own unsuccessful ABC sitcom The Bing Crosby Show in the 1964–1965 season (with co-stars Beverly Garland and Frank McHugh). The company produced two ABC medical dramas, Ben Casey (1961–1966) and Breaking Point (1963–1964), the popular Hogan's Heroes (1965–1971) military comedy on CBS, as well as the lesser-known show Slattery's People (1964–1965).

Singing style and vocal characteristics

[edit]

Crosby was one of the first singers to exploit the intimacy of the microphone rather than use the loud, penetrating vaudeville style associated with Al Jolson.[50] Crosby was, by his own definition, a "phraser", a singer who placed equal emphasis on both the lyrics and the music.[51] Paul Whiteman's hiring of Crosby, with phrasing that echoed jazz, particularly his bandmate Bix Beiderbecke's trumpet, helped bring the genre to a wider audience.[50] In the framework of the novelty-singing style of the Rhythm Boys, Crosby bent notes and added off-tune phrasing, an approach that was rooted in jazz.[52] He had already been introduced to Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith before his first appearance on record. Crosby and Armstrong remained warm acquaintances for decades, occasionally singing together in later years, e.g. "Now You Has Jazz" in the film High Society (1956). In Crosby's performances, the presence of jazz phrasing, jazz rhythm and jazz improvisation varied depending on the piece of music, but those were elements that Crosby frequently used. This can be observed particularly in his straight jazz work during the late 1920s/early 1930s, Crosby's recordings with Buddy Cole and His Trio from the mid-1950s, as well as in his numerous collaborations with such jazz musicians as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Joe Venuti, or Eddie Lang. However, while Crosby can be called a jazz singer, he was not strictly only a jazz singer as he modeled the style and techniques to a broad scope of music that he performed, ranging from Jazz to Country to even such material as operetta arias.[53]

During the early portion of his solo career (about 1931–1934), Crosby's emotional, often pleading style of crooning was popular. But Jack Kapp, manager of Brunswick and later Decca, talked Crosby into dropping many of his jazzier mannerisms in favor of a clear vocal style. Crosby credited Kapp for choosing hit songs, working with many other musicians, and most important, diversifying his repertoire into several styles and genres. Kapp helped Crosby have number one hits in Christmas music, Hawaiian music, and country music, and top-30 hits in Irish music, French music, rhythm and blues, and ballads.[54][55]

Crosby elaborated on an idea of Al Jolson's: phrasing, or the art of making a song's lyric ring true. "I used to tell Sinatra over and over," said Tommy Dorsey, "there's only one singer you ought to listen to and his name is Crosby. All that matters to him is the words, and that's the only thing that ought to for you, too."[56]

Critic Henry Pleasants wrote in 1985: [While] the octave B flat to B flat in Bing's voice at that time [1930s] is, to my ears, one of the loveliest I have heard in forty-five years of listening to baritones, both classical and popular, it dropped conspicuously in later years. From the mid-1950s, Bing was more comfortable in a bass range while maintaining a baritone quality, with the best octave being G to G, or even F to F. In a recording he made of 'Dardanella' with Louis Armstrong in 1960, he attacks lightly and easily on a low E flat. This is lower than most opera basses care to venture, and they tend to sound as if they were in the cellar when they get there.[57]

Career achievements

[edit]

Crosby's was among the most popular and successful musical acts of the 20th century. Billboard magazine used different methodologies during his career, but his chart success remains impressive: 396 chart singles, including roughly 41 number 1 hits. Crosby had separate charting singles every year between 1931 and 1954; the annual re-release of "White Christmas" extended that streak to 1957. He had 24 separate popular singles in 1939 alone. Statistician Joel Whitburn at Billboard determined that Crosby was America's most successful recording act of the 1930s and again in the 1940s.[58]

The number of Bing Crosby record sales varies. Organizations that audit record sales do not have an official tally, but some claim sales are notable, namely: In 1960, Crosby was honored as "First Citizen of Record Industry" based on having sold 200 million discs.[59] The Guinness Book reported some of the singer's worldwide sales on a few occasions: In 1973, Crosby had sold more than 400 million records worldwide, and by 1977 he had sold 500 million discs, being ranked as the most successful and best-selling musical artist in 1978.[60][61][62][63][page needed] Some sources contradict these alleged sales to the Guinness Book, as it is not an organization that counts or audits artists' sales in the United States or worldwide. According to different sources, Bing Crosby's sales number varies between: 300 million,[64] 500 million,[65] or even 1 billion, making him one of the best-selling singers in history.[66][67][page needed][68][page needed] The single "White Christmas" sold over 50 million copies according to Guinness World Records.[3]: 8

For 15 years (1934, 1937, 1940, 1943–1954), Crosby was among the top 10 acts in box-office sales, and for five of those years (1944–1948) he topped the world.[41] Crosby sang four Academy Award-winning songs—"Sweet Leilani" (1937), "White Christmas" (1942), "Swinging on a Star" (1944), "In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening" (1951)—and won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in Going My Way (1944).

A survey in 2000 found that with 1,077,900,000 movie tickets sold, Crosby was the third-most-popular actor of all time, behind Clark Gable (1,168,300,000) and John Wayne (1,114,000,000).[69] The International Motion Picture Almanac lists Crosby in a tie for second-most years at number one on the All Time Number One Stars List with Clint Eastwood, Tom Hanks, and Burt Reynolds.[70] His most popular film, White Christmas, grossed $30 million in 1954 ($340 million in current value).[71]

Crosby received 23 gold and platinum records, according to the book Million Selling Records. The Recording Industry Association of America did not institute its gold record certification program until 1958 when Crosby's record sales were low. Before 1958, gold records were awarded by record companies.[72] Crosby charted 23 Billboard hits from 47 recorded songs with the Andrews Sisters, whose Decca record sales were second only to Crosby's throughout the 1940s. They were his most frequent collaborators on disc from 1939 to 1952, a partnership that produced four million-selling singles: "Pistol Packin' Mama", "Jingle Bells", "Don't Fence Me In", and "South America, Take It Away".[73]

They made one film appearance together in Road to Rio singing "You Don't Have to Know the Language", and sang together on radio airwaves throughout the 1940s and 1950s. They appeared as guests on each other's shows and on Armed Forces Radio Service programming during and after World War II. The quartet's additional Top-10 Billboard hits from 1943 to 1945 include "The Vict'ry Polka", "There'll Be a Hot Time in the Town of Berlin (When the Yanks Go Marching In)", and "Is You Is or Is You Ain't (Ma' Baby?)" which helped the morale of the American public.[74]

In 1962, Crosby was given the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. He has been inducted into the halls of fame for both radio and popular music. In 2007, Crosby was inducted into the Hit Parade Hall of Fame and in 2008 the Western Music Hall of Fame.[75]

Popularity and influence

[edit]

Crosby's popularity around the world was such that Dorothy Masuka, the best-selling African recording artist, stated that, "Only Bing Crosby the famous American crooner sold more records than me in Africa." His great popularity throughout the continent led other African singers to emulate him, including Masuka, Dolly Rathebe, and Míriam Makeba, known locally as "The Bing Crosby of Africa".[76]

Presenter Mike Douglas commented in a 1975 interview, "During my days in the Navy in World War II, I remember walking the streets of Calcutta, India, on the coast; it was a lonely night, so far from my home and from my new wife, Gen. I needed something to lift my spirits. As I passed a Hindu sitting on the corner of a street, I heard something surprisingly familiar. I came back to see the man playing one of those old Vitrolas, like those of RCA with the horn speaker. The man was listening to Bing Crosby sing, "Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate The Positive". I stopped and smiled in grateful acknowledgment. The Hindu nodded and smiled back. The whole world knew and loved Bing Crosby."[77] His popularity in India led many Hindu singers to imitate and emulate him, notably Kishore Kumar, considered the "Bing Crosby of India".[78]

Throughout Europe and Russia, Crosby was also known as "Der Bingle", a pseudonym coined in 1944 by Bob Musel, an American journalist based in London, after Crosby had recorded three 15-minute programs with Jack Russin for broadcast to Germany from ABSIE.[79]

Entrepreneurship

[edit]According to Shoshana Klebanoff, Crosby became one of the richest men in the history of show business. He had investments in real estate, mines, oil wells, cattle ranches, race horses, music publishing, baseball teams, and television. Crosby made a fortune from the Minute Maid Orange Juice Corporation, in which he was a principal stockholder.[80]

Role in early tape recording

[edit]

During the Golden Age of Radio, performers had to create their shows live, sometimes even redoing the program a second time for the West Coast time zone. Crosby had to do two live radio shows on the same day, three hours apart, for the East and West Coasts.[81] Crosby's radio career took a significant turn in 1945, when he clashed with NBC over his insistence that he be allowed to pre-record his radio shows. The live production of radio shows was reinforced by the musicians' union and ASCAP, which wanted to ensure continued work for their members. In On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, John Dunning wrote about German engineers having developed a tape recorder with a near-professional broadcast quality standard:

[Crosby saw] an enormous advantage in prerecording his radio shows. The scheduling could now be done at the star's convenience. He could do four shows a week, if he chose, and then take a month off. But the networks and sponsors were adamantly opposed. The public wouldn't stand for 'canned' radio, the networks argued. There was something magical for listeners in the fact that what they were hearing was being performed and heard live everywhere, at that precise instant. Some of the best moments in comedy came when a line was blown and the star had to rely on wit to rescue a bad situation. Fred Allen, Jack Benny, Phil Harris, and also Crosby were masters at this, and the networks weren't about to give it up easily.

Crosby's insistence eventually factored into the further development of magnetic tape sound recording and the radio industry's widespread adoption of it.[82][83][84] He used his clout, both professionally and financially, for innovations in audio. But NBC and CBS refused to broadcast prerecorded radio programs. Crosby left the network and remained off the air for seven months, creating a legal battle with his sponsor Kraft that was settled out of court. Crosby returned to broadcasting for the last 13 weeks of the 1945–1946 season.

The Mutual Network, on the other hand, pre-recorded some of its programs as early as 1938 for The Shadow with Orson Welles. ABC was formed from the sale of the NBC Blue Network in 1943 after a federal antitrust suit and was willing to join Mutual in breaking the tradition. ABC offered Crosby $30,000 per week to produce a recorded show every Wednesday that would be sponsored by Philco. He would get an additional $40,000 from 400 independent stations for the rights to broadcast the 30-minute show, which was sent to them every Monday on three 16-inch (41 cm) lacquer discs that played ten minutes per side at 33+1/3 rpm.

Murdo MacKenzie of Bing Crosby Enterprises had seen a demonstration of the German Magnetophon in June 1947—the same device that Jack Mullin had brought back from Radio Frankfurt with 50 reels of tape, at the end of the war. It was one of the magnetic tape recorders that BASF and AEG had built in Germany starting in 1935. The 6.5 mm ferric-oxide-coated tape could record 20 minutes per reel of high-quality sound. Alexander M. Poniatoff ordered Ampex, which he founded in 1944, to manufacture an improved version of the Magnetophone.

Crosby hired Mullin to start recording his Philco Radio Time show on his German-made machine in August 1947 using the same 50 reels of I.G. Farben magnetic tape that Mullin had found at a radio station at Bad Nauheim near Frankfurt while working for the U.S. Army Signal Corps. The advantage was editing. As Crosby wrote in his autobiography:

By using tape, I could do a thirty-five- or forty-minute show, then edit it down to the twenty-six or twenty-seven minutes the program ran. In that way, we could take out jokes, gags, or situations that didn't play well and finish with only the prime meat of the show; the solid stuff that played big. We could also take out the songs that didn't sound good. It gave us a chance to first try a recording of the songs in the afternoon without an audience, then another one in front of a studio audience. We'd dub the one that came off best into the final transcription. It gave us a chance to ad-lib as much as we wanted, knowing that excess ad-libbing could be sliced from the final product. If I made a mistake in singing a song or in the script, I could have some fun with it, then retain any of the fun that sounded amusing.

Mullin's 1976 memoir of these early days of experimental recording agrees with Crosby's account:

In the evening, Crosby did the whole show before an audience. If he muffed a song then, the audience loved it—thought it was very funny—but we would have to take out the show version and put in one of the rehearsal takes. Sometimes, if Crosby was having fun with a song and not really working at it, we had to make it up out of two or three parts. This ad-lib way of working is commonplace in the recording studios today, but it was all new to us.

Crosby invested $50,000 in Ampex with the intent to produce more machines.[85] In 1948, the second season of Philco shows was recorded with the Ampex Model 200A and Scotch 111 tape from 3M.[81] Mullin explained how one new broadcasting technique was invented on the Crosby show with these machines:

One time Bob Burns, the hillbilly comic, was on the show, and he threw in a few of his folksy farm stories, which of course were not in Bill Morrow's script. Today they wouldn't seem very off-color, but things were different on radio then. They got enormous laughs, which just went on and on. We couldn't use the jokes, but Bill asked us to save the laughs. A couple of weeks later he had a show that wasn't very funny, and he insisted that we put in the salvaged laughs. Thus the laugh-track was born.

Crosby started the tape recorder revolution in America. In his 1950 film Mr. Music, Crosby is seen singing into an Ampex tape recorder that reproduced his voice better than anything else. Also quick to adopt tape recording was his friend Bob Hope. Crosby gave one of the first Ampex Model 300 recorders to his friend, guitarist Les Paul, which led to Paul's invention of multitrack recording. His organization, the Crosby Research Foundation, held tape recording patents and developed equipment and recording techniques such as the laugh track that are still in use.[85]

With Frank Sinatra, Crosby was one of the principal backers for the United Western Recorders studio complex in Los Angeles.[86]

Videotape development

[edit]Mullin continued to work for Crosby to develop a videotape recorder (VTR). Television production was mostly live television in its early years, but Crosby wanted the same ability to record that he had achieved in radio. The Fireside Theater (1950) sponsored by Procter & Gamble, was his first television production. Mullin had not yet succeeded with videotape, so Crosby filmed the series of 26-minute shows at the Hal Roach Studios, and the "telefilms" were syndicated to individual television stations.

Crosby continued to finance the development of videotape. Bing Crosby Enterprises gave the world's first demonstration of videotape recording in Los Angeles on November 11, 1951. Developed by John T. Mullin and Wayne R. Johnson since 1950, the device aired what were described as "blurred and indistinct" images, using a modified Ampex 200 tape recorder and standard quarter-inch (6.3 mm) audio tape moving at 360 inches (9.1 m) per second.[87]

Television station ownership

[edit]A Crosby-led group purchased station KCOP-TV, in Los Angeles, California, in 1954.[88] NAFI Corporation and Crosby purchased television station KPTV in Portland, Oregon, for $4 million on September 1, 1959.[89] In 1960, NAFI purchased KCOP from Crosby's group.[88] In the early 1950s, Crosby helped establish the CBS television affiliate in his hometown of Spokane, Washington. Crosby partnered with Ed Craney, who owned the CBS radio affiliate KXLY (AM) and built a television studio west of Crosby's alma mater, Gonzaga University. After it began broadcasting, the station was sold within a year to Northern Pacific Radio and Television Corporation.

Thoroughbred horse racing

[edit]Crosby was a fan of thoroughbred horse racing and bought his first racehorse in 1935. Two years later, Crosby became a founding partner of the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club and a member of its board of directors.[90][91] Operating from the Del Mar Racetrack in Del Mar, California, the group included millionaire businessman Charles S. Howard, who owned a successful racing stable that included Seabiscuit.[90] Charles' son, Lindsay C. Howard, became one of Crosby's closest friends; Crosby named his son Lindsay after him, and would purchase his 40-room Hillsborough, California, estate from Lindsay in 1965.

Crosby and Lindsay Howard formed Binglin Stable to race and breed thoroughbred horses at a ranch in Moorpark in Ventura County, California.[90] They also established the Binglin Stock Farm in Argentina, where they raced horses at Hipódromo de Palermo in Palermo, Buenos Aires. A number of Argentine-bred horses were purchased and shipped to race in the United States. On August 12, 1938, the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club hosted a $25,000 winner-take-all match race won by Charles S. Howard's Seabiscuit over Binglin's horse Ligaroti.[91] In 1943, Binglin's horse Don Bingo won the Suburban Handicap at Belmont Park in Elmont, New York. The Binglin Stable partnership came to an end in 1953 as a result of a liquidation of assets by Crosby, who needed to raise enough funds to pay the hefty federal and state inheritance taxes on his deceased wife's estate.[92] The Bing Crosby Breeders' Cup Handicap at Del Mar Racetrack is named in his honor.

Sports

[edit]Crosby had a keen interest in sports. In the 1930s, his friend and former college classmate, Gonzaga head coach Mike Pecarovich, appointed Crosby as an assistant football coach.[93] From 1946 until his death, Crosby owned a 25% share of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Although he was passionate about the team, Crosby was too nervous to watch the deciding Game 7 of the 1960 World Series, choosing to go to Paris with Kathryn and listen to its radio broadcast. Crosby had arranged for Ampex, another of his financial investments, to record the NBC telecast on kinescope. The game was one of the most famous in baseball history, capped off by Bill Mazeroski's walk-off home run that won the game for Pittsburgh. Crosby apparently viewed the complete film just once, and then stored it in his wine cellar, where it remained undisturbed until it was discovered in December 2009.[94][95] The restored broadcast was shown on MLB Network in December 2010.

Crosby was also an early investor in Bob Cobb's Billings Mustangs baseball club in 1948, joining other Hollywood stars Cecil B. DeMille, Robert Taylor, and Barbara Stanwyck who were also shareholders in the club. Crosby was also the honorary chairman of the club's board of directors.[96]

Crosby was also an avid golfer. He first took up golf at age 12 as a caddy. Crosby was already spending much time on the golf course while touring the country in a vaudeville act or with Paul Whiteman's orchestra in the mid to late 1920s. Eventually, Crosby became accomplished at the sport, at his best reaching a two handicap. Crosby competed in both the British and U.S. Amateur championships, was a five-time club champion at Lakeside Golf Club in Hollywood, and once made a hole-in-one on the 16th hole at Cypress Point.

In 1937, Crosby hosted the first 'Crosby Clambake', a pro-am tournament at Rancho Santa Fe Golf Club in Rancho Santa Fe, California, the event's location prior to World War II. After the war, the event resumed play in 1947 on golf courses in Pebble Beach, where it has been played ever since. Now the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am, the tournament is a staple of the PGA Tour, having featured Hollywood stars and other celebrities.

In 1950, Crosby became the third person to win the William D. Richardson award, which is given to a non-professional golfer "who has consistently made an outstanding contribution to golf".[97] In 1978, he and Bob Hope were voted the Bob Jones Award, the highest honor given by the United States Golf Association in recognition of distinguished sportsmanship. Crosby is a member of the World Golf Hall of Fame, having been inducted in 1978.[98]

Crosby also was a keen fisherman. In the summer of 1966, he spent a week as the guest of Lord Egremont, staying in Cockermouth and fishing on the River Derwent. Crosby's trip was filmed for The American Sportsman on ABC, although all did not go well at first as the salmon were not running. He did make up for it at the end of the week by catching a number of sea trout.[99]

In Front Royal, Virginia, a baseball stadium was named in Crosby's honor. The Front Royal Cardinals of the Valley Baseball League play their home games here. The Bing is also home to both of the county's high schools' baseball teams.

Personal life

[edit]

Crosby reportedly had an alcohol problem between the late 1920s and early 1930s, spending 60 days in jail for drinking and crashing his car during prohibition. He got his drinking under control in 1931.[3][100]

In 1977, Crosby told Barbara Walters in a televised interview that he thought marijuana should be legalized, because he believed it would make it much easier for the authorities to exert proper legal control over the market.[101]

In December 1999, the New York Post published an article by Bill Hoffmann and Murray Weiss called Bing Crosby's Single Life which claimed that "recently published" FBI files revealed connections with figures in the Mafia "since his youth".[3] However, Crosby's FBI files had already been published in 1992 and provide no indication that Crosby had ties to the Mafia except for one major, but accidental encounter in Chicago in 1929 which is not mentioned in the files, but is told by Crosby himself in his as-told-to autobiography Call Me Lucky. In the over 280 pages of Crosby's FBI files, there is only one reference to organized crime or gambling dens, the content of some of the many threats that Crosby received throughout his life.[102][103][104][105][106]

The comments made by FBI investigators in the memos discredited the claims made in the letters. In the FBI files, there is only one reference to a person associated with the Mafia. In a memorandum dated January 16, 1959, it is said: "The Salt Lake City Office has developed information indicating that Moe Dalitz received an invitation to join a deer hunting party at Bing Crosby's Elko, Nevada, ranch, together with the crooner, his Las Vegas dentist and several business associates." However, Crosby had already sold his Elko ranch a year earlier, in 1958, and it is doubtful how much he was really involved in that meeting.[107][108][104][105][109]

Romantic relationships

[edit]Crosby was married twice. His first wife was actress and nightclub singer Dixie Lee, to whom he was married from 1930 until she died of ovarian cancer in 1952. They had four sons: Gary, twins Dennis and Phillip, and Lindsay. Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman (1947) was rumored to be based on Lee's life. The Crosby family lived at 10500 Camarillo Street in North Hollywood for more than five years.[110]

After his wife died, Crosby had relationships with model Pat Sheehan, who married his son Dennis in 1958, and actresses Inger Stevens and Grace Kelly. Crosby married actress Kathryn Grant, who converted to Catholicism, in 1957.[111] They had three children: Harry Lillis III, who played Bill in Friday the 13th, Mary Frances, best known for portraying Kristin Shepard on TV's Dallas, and Nathaniel, the 1981 U.S. Amateur champion in golf.[112]

Particularly during the late 1930s and the 1940s, Crosby's domestic life was dominated by his wife's excessive drinking. His efforts to cure her with the help of specialists failed. Tired of Dixie's drinking, Crosby even asked her for a divorce in January 1941. During the 1940s, he consistently had difficulties trying to stay away from home, while also trying to be there as much as possible for his children.[113]

Crosby had one confirmed extramarital affair between 1945 and the late 1940s, while married to his first wife Dixie. Actress Patricia Neal, who herself at the time was having an affair with the married Gary Cooper, wrote in her 1988 autobiography As I Am about a cruise to England with actress Joan Caulfield in 1948:

She [Caulfield] was a lovely girl and we had some good talks. She, too, was in love with an older married man who was quite as famous as Gary [Cooper]. She confided to me that she desperately wanted to marry Bing Crosby. We were in the same boat in more ways than one, but I could not tell her so.[114]

In the 2018 Crosby biography Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star; the War Years, 1940–1946, there are excerpts from an original diary of two sisters, Violet and Mary Barsa, who, as young women, used to stalk Crosby in New York City in December 1945 and January 1946, and who detailed their observations in the diary. The document reveals that, during that time, Crosby was taking Caulfield out to dinner, visited theaters and opera houses with her, and Caulfield and a person in her company entered the Waldorf Hotel where Crosby was staying. The document also clearly indicates that at their meetings a third person, in most instances, Caulfield's mother, was present. In 1954, Caulfield admitted to a relationship with a "top film star" who was a married man with children, who, in the end, chose his wife and children over her.[113]

Caulfield's sister, Betty Caulfield, confirmed the romantic relationship between Caulfield and Crosby. Despite being a Catholic, Crosby was seriously considering divorce in order to marry Caulfield. Either in December 1945 or January 1946, Crosby approached Cardinal Francis Spellman with his difficulties with dealing with his wife's alcoholism, his love for Caulfield and his plan to file for divorce. According to Betty Caulfield, Spellman told Crosby: "Bing, you are Father O'Malley and under no circumstances can Father O'Malley get a divorce." Around the same time, Crosby talked to his mother about his intentions and she protested. Ultimately, Crosby chose to end the relationship and to stay with his wife. Crosby and Dixie reconciled, and he continued trying to help her overcome her alcohol issues.[113]

Homes

[edit]In November 1958, Crosby purchased the 1,350-acre Rising River Ranch in Cassel, California after renting a portion of it for several years.[115] Attorney Ira Shadwell declined to disclose the purchase price. In October 1978, actor Clint Eastwood purchased the ranch under the name of his business manager, Roy Kaufman, for $1.5 million.[116]

Crosby and his family lived in the San Francisco area for many years. In 1963, he and his wife Kathryn moved with their three young children from Los Angeles to a $175,000 ten-bedroom Tudor estate in Hillsborough, formerly owned by fellow horseman Lindsay C. Howard, one of Crosby's closest friends, because they did not want to raise their children in Hollywood, according to son Nathaniel. This house went up for sale by its current owners in 2021 for $13.75 million.[117][118]

In 1965, the Crosbys moved to a larger, 40-room French chateau-style house on nearby Jackling Drive, where Kathryn Crosby continued to reside after Bing's death.[119] This house served as a setting for some of the family's Minute Maid orange juice television commercials.[117]

Children

[edit]After Crosby's death, his eldest son, Gary, published a highly critical memoir, Going My Own Way (1983; written in collaboration with noted music journalist Ross Firestone), depicting his father as cruel, cold, remote, and physically and psychologically abusive.[120] While acknowledging that corporal punishments took place, there were reports of all of Gary's immediate siblings distancing themselves from the abuse claims, either in public or in private.[113]

Crosby's younger son Phillip disputed his brother Gary's claims about their father. Around the time Gary published his claims, Phillip stated to the press that "Gary is a whining, bitching crybaby, walking around with a two-by-four on his shoulder and just daring people to nudge it off."[121] Nevertheless, Phillip did not deny that Crosby believed in corporal punishment.[121] In an interview with People magazine, Phillip stated that "we never got an extra whack or a cuff we didn't deserve".[121]

Shortly before Gary's book was actually published, Lindsay said, "I'm glad [Gary] did it. I hope it clears up a lot of the old lies and rumors."[113][121] Unlike Gary, Lindsay stated that he preferred to remember "all the good things I did with my dad and forget the times that were rough".[121] "Lindsay Crosby supported his brother (Gary) at the time of its publication but had a tempered view of its revelations. 'I never expected affection from my father so it didn't bother me,' he once told an interviewer.'"[122] However, after the book was published, Lindsay addressed the abuse claims and what the media had made out of them:

He was a good father. It was a happy childhood. We had our differences, but we were raised to respect our parents, to do what they said. If we didn't, we got punished. As far as I know [Gary] wrote it because it was about himself and what he felt his life was about. I don't think it had anything to do with Daddy Dearest. I understand what he's trying to prove. I don't think he did anything wrong.[123]

Dennis Crosby reportedly "said his older brother (Gary) was the most severely treated of the four boys. 'He got the first licking, and we got the second.'"[124]

Gary's first wife of 19 years, Barbara Cosentino, of whom Gary wrote in his book, "I could confide in her about Mom and Dad and my childhood",[125] and with whom Gary stayed friendly after the divorce, stated:

I do not know if what's in the book is true but he never said anything to me about whippings. I think it all got a little out of hand. I certainly never witnessed anything between him and his father. I couldn't believe it when I read the book because it just didn't sound like Gary. I can't pinpoint it. Gary said to me before I read it, "It's not the same book I wrote."[123]

Gary Crosby's adopted son, Steven Crosby, said in a 2003 interview:

In the early years, I think, like any family you are going to butt heads with your mom, your dad and your brothers and sisters. I think there was some father–son stuff that everyone has. The book was I think an attempt of my dad to come to grips with some things in his life.[126]

Bing's younger brother, singer and jazz bandleader Bob Crosby, recalled at the time of Gary's revelations that Bing was a "disciplinarian", as their mother and father had been. He added, "We were brought up that way."[121] In an interview for the same article, Gary clarified that Bing "was like a lot of fathers of that time. He was not out to be vicious, to beat children for his kicks."[121]

The author of the 2018 biography on Bing Crosby, Gary Giddins, claims that Gary Crosby's memoir is not reliable on many instances and cannot be trusted on the abuse stories.[113][127]

Crosby's will established a blind trust in which none of the sons received an inheritance until they reached the age of 65, intended by Crosby to keep them out of trouble.[128] They instead received several thousand dollars per month from a trust left in 1952 by their mother, Dixie Lee. The trust, tied to high-performing oil stocks, folded in December 1989 following the 1980s oil glut.[129]

Lindsay Crosby died in 1989 at age 51, and Dennis Crosby died in 1991 at age 56, both by suicide from self-inflicted gunshot wounds. Gary Crosby died of lung cancer in 1995 at age 62. Phillip Crosby died of a heart attack in 2004 at age 69.[130]

Nathaniel Crosby, Crosby's younger son from his second marriage, is a former high-level golfer who won the U.S. Amateur in 1981 at age 19, becoming the youngest winner in the history of that event at the time. Harry Crosby is an investment banker who occasionally makes singing appearances.

Denise Crosby, Dennis Crosby's daughter, is an actress and is known for her role as Tasha Yar on Star Trek: The Next Generation. She appeared in the 1989 film adaptation of Stephen King's novel Pet Sematary.

In 2006, Crosby's niece through his sister Mary Rose, Carolyn Schneider, published the laudatory book Me and Uncle Bing.

Disputes between Crosby's two families began in the late 1990s. When Dixie died in 1952, her will provided that her share of the community property be distributed in trust to her sons. After Crosby's death in 1977, he left the residue of his estate to a marital trust for the benefit of his widow, Kathryn, and HLC Properties, Ltd., was formed for the purpose of managing his interests, including his right of publicity. In 1996, Dixie's trust sued HLC and Kathryn for declaratory relief as to the trust's entitlement to interest, dividends, royalties, and other income derived from the community property of Crosby and Dixie.

In 1999, the parties settled for approximately $1.5 million. Relying on a retroactive amendment to the California Civil Code, Dixie's trust brought suit again, in 2010, alleging that Crosby's right of publicity was community property, and that Dixie's trust was entitled to a share of the revenue it produced. The trial court granted Dixie's trust's claim. The California Court of Appeals reversed it, holding that the 1999 settlement barred the claim. In light of the court's ruling, it was unnecessary for the court to decide whether a right of publicity can be characterized as community property under California law.[131]

Health and death

[edit]

Following his recovery from a life-threatening fungal infection in his right lung in January 1974, Crosby emerged from semi-retirement to start a new spate of albums and concerts. On March 20, 1977, after videotaping a CBS concert special, "Bing – 50th Anniversary Gala", at the Ambassador Auditorium with Bob Hope looking on, Crosby fell off the stage into an orchestra pit, rupturing a disc in his back requiring a month-long stay in the hospital.[132] Crosby's first performance after the accident was his last American concert, on August 16, 1977, the day Elvis Presley died, at the Concord Pavilion in Concord, California. When the electric power failed during his performance, Crosby continued singing without amplification.[133] On August 27, Crosby gave a televised concert in Norway.[134]

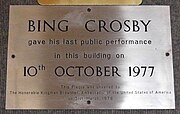

In September, Crosby, his family and singer Rosemary Clooney began a concert tour of Britain that included two weeks at the London Palladium. While in the UK, Crosby recorded his final album, Seasons, and his final TV Christmas special with guest David Bowie on September 11, which aired a little over a month after Crosby's death. Crosby's last concert was in the Brighton Centre on October 10, four days before his death, with British entertainer Gracie Fields in attendance. The following day, Crosby made his final appearance in a recording studio and sang eight songs at the BBC's Maida Vale Studios for a radio program, which included an interview with Alan Dell.[135] Accompanied by the Gordon Rose Orchestra, Crosby's last recorded performance was of the song "Once in a While". Later that afternoon, he met with Chris Harding to take photographs for the Seasons album jacket.[135]

On October 13, 1977, Crosby flew alone to Spain to play golf and hunt partridge.[136] The next day, Crosby played 18 holes of golf at the La Moraleja Golf Course near Madrid. His partner was World Cup champion Manuel Piñero. Their opponents were club president César de Zulueta and Valentín Barrios.[136] According to Barrios, Crosby was in good spirits throughout the day, and was photographed several times during the round.[136][137] At the ninth hole, construction workers building a house nearby recognized Crosby, and when asked for a song, Crosby sang "Strangers in the Night".[136] Crosby, who had a 13 handicap, won with his partner by one stroke.[136]

As Crosby and his party headed back to the clubhouse at around 6:30 p.m., Crosby said, "That was a great game of golf, fellas. Let's go have a Coca-Cola." Those were his last words.[136] About 20 yards (18 m) from the clubhouse entrance, Crosby collapsed and died instantly from a massive heart attack.[138] At the clubhouse and later in the ambulance, house physician Dr. Laiseca tried to revive him, but was unsuccessful. At Reina Victoria Hospital, Crosby was administered the last rites of the Catholic Church and was pronounced dead at the age of 74.[136]

On October 18, 1977, following a private funeral Mass at St. Paul the Apostle Catholic Church in Westwood, Los Angeles,[139] Crosby was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California.[140]

Legacy

[edit]

Crosby is a member of the National Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame in the radio division.[141]

The family created an official website[142] on October 14, 2007, the 30th anniversary of Crosby's death.

In his autobiography Don't Shoot, It's Only Me! (1990), Bob Hope wrote, "Dear old Bing, as we called him, the Economy-sized Sinatra. And what a voice. God I miss that voice. I can't even turn on the radio around Christmas time without crying anymore."[143]

Calypso musician Roaring Lion wrote a tribute song in 1939 titled "Bing Crosby", in which he wrote: "Bing has a way of singing with his very heart and soul / Which captivates the world / His millions of listeners never fail to rejoice / At his golden voice...."[3]

Bing Crosby Stadium in Front Royal, Virginia, was named after Crosby in honor of his fundraising and cash contributions for its construction from 1948 to 1950.[144]

In 2006, the former Metropolitan Theater of Performing Arts ('The Met') in Spokane, Washington, was renamed to The Bing Crosby Theater.[145]

Crosby has three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. One each for radio, recording, and motion pictures.

Compositions

[edit]Crosby wrote or co-wrote lyrics to 22 songs. His composition "At Your Command" was number 1 for three weeks on the U.S. pop singles chart beginning on August 8, 1931. "I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You" was his most successful composition, recorded by Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra, Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, and Mildred Bailey, among others. Songs co-written by Crosby include:

- "That's Grandma" (1927), with Harry Barris and James Cavanaugh

- "From Monday On" (1928), with Harry Barris and recorded with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra featuring Bix Beiderbecke on cornet, number 14 on US pop singles charts

- "What Price Lyrics?" (1928), with Harry Barris and Matty Malneck

- "Ev'rything's Agreed Upon" (1930), with Harry Barris[146]

- "At Your Command" (1931), with Harry Barris and Harry Tobias, US, number 1 (3 weeks)

- "Believe Me" (1931), with James Cavanaugh and Frank Weldon[146]

- "Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day)" (1931), with Roy Turk and Fred Ahlert, US, no. 4; US, 1940 re-recording, no. 27

- "You Taught Me How to Love" (1931), with H. C. LeBlang and Don Herman[146]

- "I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You" (1932), with Victor Young and Ned Washington, US, no. 5

- "My Woman" (1932), with Irving Wallman and Max Wartell

- "Cutesie Pie" (1932), with Red Standex and Chummy MacGregor[146]

- "I Was So Alone, Suddenly You Were There (1932), with Leigh Harline, Jack Stern and George Hamilton[146]

- "Love Me Tonight" (1932), with Victor Young and Ned Washington, US, no. 4

- "Waltzing in a Dream" (1932), with Victor Young and Ned Washington, US, no.6

- "You're Just a Beautiful Melody of Love" (1932), lyrics by Bing Crosby, music by Babe Goldberg

- "Where Are You, Girl of My Dreams?"[147] (1932), written by Bing Crosby, Irving Bibo, and Paul McVey, featured in the 1932 Universal film The Cohens and Kellys in Hollywood

- "I Would If I Could But I Can't" (1933), with Mitchell Parish and Alan Grey

- "Where the Turf Meets the Surf" (1941) with Johnny Burke and James V. Monaco.

- "Tenderfoot" (1953) with Bob Bowen and Perry Botkin, originally issued using the pseudonym of "Bill Brill" for Bing Crosby.

- "Domenica" (1961) with Pietro Garinei / Gorni Kramer / Sandro Giovannini

- "That's What Life is All About" (1975), with Ken Barnes, Peter Dacre, and Les Reed, US, AC chart, no. 35; UK, no. 41

- "Sail Away from Norway" (1977) – Crosby wrote lyrics to go with a traditional song.

Grammy Hall of Fame

[edit]Four performances by Bing Crosby have been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, which is a special Grammy award established in 1973 to honor recordings that are at least 25 years old and that have "qualitative or historical significance".

| Bing Crosby: Grammy Hall of Fame[148] | |||||

| Year Recorded | Title | Genre | Label | Year Inducted | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | "White Christmas" | Traditional Pop (single) | Decca | 1974 | With the Ken Darby Singers |

| 1944 | "Swinging on a Star" | Traditional Pop (single) | Decca | 2002 | With the Williams Brothers Quartet |

| 1936 | "Pennies from Heaven" | Traditional Pop (single) | Decca | 2004 | With the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra |

| 1944 | "Don't Fence Me In" | Traditional Pop (single) | Decca | 1998 | With the Andrews Sisters |

Discography

[edit]Filmography

[edit]Television appearances

[edit]Radio

[edit]- 15 Minutes with Bing Crosby[149] (1931, CBS), Unsponsored. 6 nights a week, 15 minutes.

- The Cremo Singer (1931–1932, CBS),[150] 6 nights a week, 15 minutes.

- 15 Minutes with Bing Crosby (1932, CBS), initially 3 nights a week, then twice a week, 15 minutes.

- Chesterfield Cigarettes Presents Music that Satisfies[151] (1933, CBS), broadcast two nights a week, 15 minutes.

- Bing Crosby Entertains[152] (1933–1935, CBS), weekly, 30 minutes.

- Kraft Music Hall[153] (1935–1946, NBC), Thursday nights, 60 minutes until January 1943, then 30 minutes.

- Bing Crosby on Armed Forces Radio in World War II (1941–1945; World War II).[154]

- Philco Radio Time[155] (1946–1949, ABC), 30 minutes weekly.

- This Is Bing Crosby (The Minute Maid Show) (1948–1950, CBS), 15 minutes each weekday morning; Bing as disc jockey.

- The Bing Crosby – Chesterfield Show[156] (1949–1952, CBS), 30 minutes weekly.

- The Bing Crosby Show for General Electric[157] (1952–1954, CBS), 30 minutes weekly.

- The Bing Crosby Show (1954–1956)[158] (CBS), 15 minutes, 5 nights a week.

- A Christmas Sing with Bing (1955–1962), (CBS, VOA and AFRS), 1 hour each year, sponsored by the Insurance Company of North America.

- The Ford Road Show Featuring Bing Crosby[159] (1957–1958, CBS), 5 minutes, 5 days a week.

- The Bing Crosby – Rosemary Clooney Show[160] (1960–1962, CBS), 20 minutes, 5 mornings a week, with Rosemary Clooney.

RIAA certification

[edit]| Album | RIAA[161] |

| Merry Christmas (1945) | Gold |

| White Christmas (re-issue of album above) (1995) | 4× Platinum |

| Bing Sings (1977) | 2× Platinum |

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Award | Category/Status | Project/Team | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Actor | Going My Way | Won |

| 1944 | Photoplay Awards | Most Popular Male Star | — | Won |

| 1945 | — | Won | ||

| 1945 | Academy Awards | Best Actor in a Leading Role | Going My Way | Won |

| 1946 | Photoplay Awards | Most Popular Male Star | — | Won |

| 1946 | Academy Awards | Best Actor in a Leading Role | The Bells of St. Mary's | Nominated |

| 1947 | Photoplay Awards | Most Popular Male Star | — | Won |

| 1948 | — | Won | ||

| 1952 | Golden Globes | Best Motion Picture Actor | Here Comes the Groom | Nominated |

| 1954 | National Board of Review | Best Actor | The Country Girl | Won |

| 1955 | Academy Awards | Best Actor in a Leading Role | Nominated | |

| 1958 | Laurel Awards | Golden Laurel Top Male Star | — | Nominated |

| 1959 | — | Nominated | ||

| 1960 | Golden Laurel Top Male Performance | Say One for Me | Nominated | |

| 1960 | Golden Globe Awards | Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award | — | Won |

| 1960 | Hollywood Walk of Fame | Radio | 6769 Hollywood Blvd. | Inducted |

| 1960 | Recording | 6751 Hollywood Blvd. | Inducted | |

| 1960 | Motion Picture | 1611 Vine Street. | Inducted | |

| 1960 | 1960 World Series | Co-owner | Pittsburgh Pirates | Won |

| 1961 | Laurel Awards | Golden Laurel Top Male Star | — | Nominated |

| 1962 | Golden Laurel Special Award | — | Won | |

| 1963 | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award | Won | ||

| 1970 | Peabody Awards | Personal Award | — | Won |

| 1971 | 1971 World Series | Co-owner | Pittsburgh Pirates | Won |

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Communications, Museum of Broadcast (2004). The Museum of Broadcast Communications Encyclopedia of Radio. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 978-1-57958-431-3.

- ^ Prigozy, Ruth; Raubicheck, Walter (2007). Going My Way: Bing Crosby and American Culture. University Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-261-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Giddins, Gary (2001). Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams (1 ed.). Little, Brown. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-316-88188-0.

- ^ "Bing Crosby – Hollywood Star Walk". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Young, Larry (October 15, 1977). "Bing Crosby dies of heart attack". Spokesman-Review. p. 1.

- ^ Gilliland 1994, cassette 1 side B.

- ^ Giddins, Gary (January 28, 2001). "MUSIC; Bing Crosby, The Unsung King of Song". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Giddins, Gary (2018). Bing Crosby – Swinging on a Star – The War Years 1940–1946. New York: Little, Brown & Co. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-316-88792-2.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Frank. "Crooner". Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ^ a b Stanley, Bob, Let's Do It: The Birth of Pop Music, Pegasus Books, 2022, pg. 220

- ^ Tapley, Krostopher (December 10, 2015). "Sylvester Stallone Could Join Exclusive Oscar Company with 'Creed' Nomination". Variety. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ "Hollywood Star Walk". Projects.latimes.com.

- ^ "Bing Crosby". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019.

- ^ "Engineering and Technology History Wiki". Ethw.org. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Grudens, 2002, p. 236. "Bing was born on May 3, 1903. He always believed he was born on May 2, 1904."

- ^ Giddins, Gary. "Bing Bio – Bing Crosby". Bingcrosby.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Blecha, Peter (August 29, 2005). "Crosby, Bing (1903–1977) and Mildred Bailey (1907–1951), Spokane". Historylink.org. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Gonzaga History 1980–1989 (September 17, 1986). "Gonzaga History 1980–1989 – Gonzaga University". Gonzaga.edu. Archived from the original on December 7, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bing Crosby House Museum". Gonzaga.edu. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Bing Crosby and Gonzaga University: 1903–1925. "Bing Crosby and Gonzaga University: 1903–1925 – Gonzaga University". Gonzaga.edu. Archived from the original on August 9, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Macfarlane, Malcolm (2001). Bing Crosby – Day by Day. Lanham. Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-8108-4145-2.

- ^ "Bing Crosby ~ Timeline: Bing Crosby's Life and Career". American Masters – PBS. December 2014. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ Her Heart Can See: The Life and Hymns of Fanny J. Crosby By Edith L. Blumhofer, Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer pg. 4

- ^ Macfarlane, Malcolm (2001). Bing Crosby – Day by Day. Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-8108-4145-2.

- ^ Giddins, Gary (2002). Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams, The Early Years 1903–1940. Back Bay Books. p. 24.

- ^ Gilliland 1994, cassette 3, side B.

- ^ Kershner, Jim (February 21, 2007). "Gonzaga University". HistoryLink.org. Essay 8097. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ "Bing Crosby and Gonzaga University: 1903–1925". Gonzaga University, via Internet Archive. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Bing Crosby comes home to his Gonzaga". Spokane Daily Chronicle. October 21, 1937. p. 1.

- ^ Plowman, Stephanie. "LibGuides: Manuscript Collections: Crosby". Researchguides.gonzaga.edu. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "She Loves Me Not, starring Bing Crosby and Nan Grey". Free-classic-radio-shows.com. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Goldin, J. David (May 3, 2018). "The Lux Radio Theatre". Radiogoldindex.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Associated Press (February 1, 1932). "Harry Crosby Got Nickname from Cartoon; Started as 'Bingville' and Was Later Shortened to Bing". The Binghamton Press. p. 17. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Crosby, Bing; Martin, Pete (1953). Call Me Lucky. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 19.

- ^ Thompson, Charles (1975). Bing: The Authorized Biography. London: W. H. Allen. p. 5. ISBN 9780491017152.

- ^ Early KHQ broadcast from the Davenport Hotel Spokane

- ^ a b Macfarlane, Malcolm (2001). Bing Crosby: Day by Day (Live (online) revision ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810841452.

- ^ "Paul Whiteman's Original Rhythm Boys". Redhotjazz.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ Macfarlane, Malcolm. "Bing Crosby – Day by Day". BING magazine. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ "Bing Crosby". Radio Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Bing Crosby at AllMusic

- ^ "Bing Crosby- Bing! His Legendary Years How's the sound? | Steve Hoffman Music Forums". Forums.stevehoffman.tv. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ "Pennies from Heaven (1936)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c Barnett, Lincoln (June 18, 1945). "Bing Inc". Stevenlewis.info. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Time Inc (June 18, 1945). Life. pp. 17–. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ a b British Hit Singles & Albums (2005 ed.). Guinness. May 2005. p. 126. ISBN 1-904994-00-8.

- ^ Radio & TV York Daily Record. December 19, 1958. p. 56.

- ^ Fisher, James (Spring 2012). "Bing Crosby: Through the Years, Volumes One–Nine (1954–56)". ARSC Journal. 43 (1).

- ^ Pairpoint, Lionel. "The Chronological Bing Crosby on Television". BING magazine. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Giddins, Gary (January 28, 2001). "Bing Crosby: The Unsung King of Song". The New York Times. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ "Bing Crosby (1901?–1977)". Music Educators Journal (7) (64 ed.): 56–57. 1978.

- ^ Giddins, Gary, Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams, The Early Years, 1903-1940, (NY: Little and Brown, 2009), p. 67, ISBN 0316091561

- ^ Gary Giddins, Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams, The Early Years, 1903-1940, (NY: Little and Brown, 2009), ISBN 0316091561

- ^ Gilliland 1994, cassette 1, side B.

- ^ "Jack Kapp – Bing Crosby Internet Museum". Stevenlewis.info. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ Friedwald, Will (November 2, 2010). A Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Singers. Knopf Doubleday. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-0-307-37989-4. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ Pleasants, Henry (1985). The Great American Popular Singers. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ Don Tyler, Music of the Postwar Era (NY: ABC-CLIO, 2008), 209. ISBN 9780313341915

- ^ Nathaniel Crosby; John Strege (May 3, 2016). 18 Holes with Bing: Golf, Life, and Lessons from Dad. Dey Street Books. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-06-241430-4.

- ^ Billboard , 2001

- ^ O'Connor, Ohn J. (May 25, 1978). "TV: 'Bing Crosby. His Life and Legend'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ The New York Times . 1993. «Television; Bing Crosby's 2 Lives: In Public and in Private».

- ^ Norris (1978). Guinness Book of World Records 1978.

- ^ SPIN. April 1992. pp. 57–. ISSN 0886-3032.

- ^ Brady, Bradford; Maron, John (March 1, 2020). "On the Record: How did Bing Crosby get his nickname?". Bristol Herald Courier. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021.

- ^ The New York Times. (1993). «Review Bing Crosby's 2 Lives: In Public and in Private».

- ^ America in the 20th Century . Cavendish.

- ^ Abjorensen , ( 2017). Historical of Popular Music .

- ^ Macfarlane, Malcolm (2001). Bing Crosby – Day by Day. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 670–671. ISBN 0-8108-4145-2.

- ^ "Top Ten Money Making Stars of the past 79 years". Quigley Publishing. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Schmidt, Wayne. "Waynes This and That". Waynesthisandthat.com. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ Erich Hertz and Jeffrey Roessner, Write in Tune: Contemporary Music in Fiction (NY: Bloomsbury, 2014), 2-3. ISBN 9781623561451

- ^ Sforza, John: "Swing It! The Andrews Sisters Story". University Press of Kentucky. 2000.[page needed]

- ^ Sforza, John: "Swing It! The Andrews Sisters Story". University Press of Kentucky. 2000.[page needed]

- ^ "Bing Crosby – Western Music Association Hall of Fame". Westernmusic.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Music, International Association for the Study of Popular (August 1998). Popular Music: Intercultural Interpretations. Graduate Program in Music, Kanazawa University. ISBN 978-4-9980684-1-9.

- ^ Douglas, Mike; Kelly, Thomas; Heaton, Michael (2000). I'll be Right Back: Memories of TV's Greatest Talk Show. Thorndike Press. ISBN 978-0-7862-2358-9.

- ^ Plantenga, Bart (September 13, 2013). Yodel-Ay-Ee-Oooo: The Secret History of Yodeling Around the World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-71665-2.

- ^ "Day by Day by Malcolm Macfarlane, see August 31, 1944".

- ^ Klebanoff, Shoshana, "Crosby, Bing" American National Biography (2000).

- ^ a b Careless, James (May 22, 2019). "The Ever-Evolving Role of Airchecks". Radio World. Vol. 43, no. 13. p. 18.