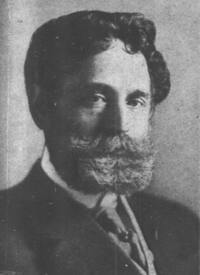

J. Hamilton Lewis

J. Hamilton Lewis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Senate Majority Whip | |

| In office March 4, 1933 – April 9, 1939 | |

| Leader | Joe Robinson Alben W. Barkley |

| Preceded by | Simeon D. Fess |

| Succeeded by | Sherman Minton |

| In office May 28, 1913 – March 3, 1919 | |

| Leader | John W. Kern Thomas S. Martin |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Charles Curtis |

| United States Senator from Illinois | |

| In office March 4, 1931 – April 9, 1939 | |

| Preceded by | Charles S. Deneen |

| Succeeded by | James M. Slattery |

| In office March 26, 1913 – March 3, 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Shelby Cullom |

| Succeeded by | Medill McCormick |

| Corporation Counsel of Chicago | |

| In office 1905–1907 | |

| Mayor | Edward Fitzsimmons Dunne |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Washington's at-large district | |

| In office March 4, 1897 – March 3, 1899 | |

| Preceded by | William H. Doolittle |

| Succeeded by | Francis W. Cushman |

| Member of the Washington Territorial Legislature | |

| In office 1887–1888 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Hamilton Lewis May 18, 1863 Danville, Virginia, C.S. |

| Died | April 9, 1939 (aged 75) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Fort Lincoln Cemetery, Brentwood, Maryland |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Rose Lawton Douglas

(m. 1896; death 1939) |

| Education | University of Virginia Ohio Northern University Baylor University |

| Occupation | Attorney |

James Hamilton Lewis (May 18, 1863 – April 9, 1939) was an American attorney and politician. Sometimes referred to as J. Ham Lewis or Ham Lewis, he represented Washington in the United States House of Representatives, and Illinois in the United States Senate. He was the first to hold the title of Whip in the United States Senate.

Born in Danville, Virginia and raised in Augusta, Georgia, Lewis attended several colleges, studied law, and attained admission to the bar in 1882. He moved to Washington Territory in 1885, where he became active in politics as a Democrat; he served in the territorial legislature, worked with the federal commission that helped establish the U.S.-Canada boundary, and ran unsuccessfully for governor. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1897 to 1899.

After service in the Spanish–American War, Lewis relocated to Chicago, Illinois. After serving as the city's corporation counsel, and running unsuccessfully for governor, Lewis won election to the United States Senate in 1913, and served one term (1913-1919). He was chosen to serve as Majority Whip, and was the first person to hold this position. He ran unsuccessfully for reelection in 1918, and for governor in 1920. In 1930, he was again elected to the U.S. Senate, and served from 1931 until his death. He died in Washington, D.C., and was interred first in Arlington, Virginia, and later at Fort Lincoln Cemetery in Brentwood, Maryland.

Early life

[edit]Lewis was born in Danville, Virginia on May 18, 1863, and grew up in Augusta, Georgia.[1] His mother had traveled to Virginia to nurse his father, who was wounded while serving for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. His mother died in childbirth, and his father was left an invalid, so Lewis was raised by relatives.[2] He attended Augusta's Houghton School, the University of Virginia, Ohio Northern University and Baylor University, and studied law in Savannah, Georgia.[1] He was admitted to the bar in 1882, and moved to Seattle in 1885, where he continued to practice law.[1] A Democrat, he served in Washington Territory's legislature from 1887 to 1888. In 1889 and 1890, Lewis worked with the Joint High Commission on Canadian and Alaska Boundaries to present the U.S. position.[1] He was an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Washington in 1892.[1]

Continued career

[edit]Lewis was one of the few politicians to represent two states in the United States Congress. He represented Washington (1897–1899) in the United States House of Representatives, and was an unsuccessful candidate for election in 1898.[1] In 1899, he served as a U.S. Commissioner for regulating customs laws between the United States and Canada, and was an unsuccessful candidate for the United States Senate.[1] During the Spanish–American War, Lewis served on the staff of the adjutant general of the Washington National Guard as an assistant inspector general with the rank of lieutenant colonel.[1] He was subsequently promoted to colonel, and served in a similar role in Cuba on the staff of John R. Brooke, followed by service on the staff of Frederick Dent Grant.[1]

In 1896, Lewis received 11 votes for the vice presidential nomination on the first ballot at the Democratic National Convention despite not yet having attained the constitutionally required minimum age of 35.[3] In 1900, he was an unsuccessful candidate for the Democratic vice presidential nomination;[1] he withdrew before the balloting, and the nomination was won by Adlai Stevenson.[4] In 1903, Lewis relocated to Chicago, where he continued to practice law, and served as the city's corporation counsel from 1905 to 1907.[1] In 1908, he was an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Illinois.[1]

In 1913, Lewis was elected to the U.S. Senate from Illinois; he served one term (1913–1919), and was the Majority Whip for his entire term. In 1914, he was the Senate's representative at a London conference that considered way to ensure that laws and treaties guaranteeing safe sea travel could still be implemented as World War I was beginning.[1] Lewis also served as chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in the Department of State from 1915 to 1919.[1] A close ally of President Woodrow Wilson, Lewis was a leader in getting much of Wilson's "New Freedom" legislation passed. Lewis also performed unspecified special wartime duties in Europe which led to him receiving knighthoods from the kings of Belgium and Greece.[1] In October 1918, Lewis was aboard an army ship, USS Mount Vernon, when it was hit by German fire.[5] Lewis and others survived the blast, but 35 of the ship's crewmen perished.[6]

Upon his defeat for reelection in 1918, Lewis was offered the ambassadorship to Belgium, but he declined and returned to private legal practice in Chicago, Illinois. In 1920, he ran unsuccessfully for governor. He eventually became a partner in the newly named Lewis, Adler, Lederer & Kahn (now known as Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr, LLP).[7]

In 1921, 1922, and 1925, Lewis was part of the U.S. delegation to League of Nations conferences held to settle wartime damage claims.[9]

Later career

[edit]In 1930, Lewis was again elected to the Senate; he was reelected in 1936 and served from March 4, 1931, until his death.[9] He again served as the Majority Whip, this time from 1933 until his death. In addition, he was chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in Executive Departments from 1933 until his death.[9]

In 1932, Lewis went to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, as the "favorite son" candidate of Illinois, at the behest of Chicago mayor Anton Cermak. Cermak's hope was to use Lewis to keep the Illinois delegates from supporting Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but Lewis later withdrew his name from consideration and released his delegates, many of whom went to FDR and helped secure him the nomination.[10]

As a member of the foreign relations committee, he told the Associated Press in 1938 that Hitler was not going to fight over Czechoslovakia saying, "(Czechoslovakia) is a small matter that could be settled at any time." Sixteen days later Hitler annexed parts of Czechoslovakia, with the assent of Great Britain and France.[11]

Lewis was one of the first to befriend Harry S. Truman after Truman's election to the Senate. During Truman's first few weeks in office in 1935, Lewis sat next to Truman and advised him: "Harry, don't start out with an inferiority complex. For the first six months you'll wonder how the hell you got here. After that you'll wonder how the hell the rest of us got here."[12]

Personal life

[edit]In 1896, Lewis married Rose Lawton Douglas (1871–1972).[13] Lewis was known to be something of an eccentric in manner and dress, wearing spats well into the 1930s even though they were out of fashion, and sporting Van Dyke whiskers during an era when most men were clean shaven, as well as a collection of "wavy pink toupees".[14] He was courtly in manner, and while some considered him verbose, he was generally acknowledged to be a talented orator.[15][16][17]

Death and burial

[edit]Lewis died at Garfield Hospital in Washington, DC, and his funeral service was held in the Senate Chamber.[9] He was interred at the Abbey Mausoleum near Arlington National Cemetery;[9] he was later reinterred at Fort Lincoln Cemetery in Brentwood, Maryland.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o James Hamilton Lewis, Late a Senator from Illinois, p. 5.

- ^ Kirby, Bill (December 20, 2021). "Monday Mystery: Headlines followed U.S. Sen. Hamilton Lewis until he vanished into history". The Augusta Chronicle. Augusta, GA.

- ^ "Sewell of Maine Nominated". Los Angeles Evening Express. Los Angeles, CA. July 11, 1896. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Stevenson Chosen as Mate for Bryan". The Lincoln Evening News. Lincoln, NE. July 6, 1900. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1918

- ^ Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1918

- ^ Chicago Tribune, November 11, 1923

- ^ Taylor, Julius F. "The Broad Ax". Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e James Hamilton Lewis, Late a Senator from Illinois, p. 6.

- ^ Hill, Ray (December 16, 2012). "The Senate's Dandy: James Hamilton Lewis of Illinois - The Knoxville Focus". The Knoxville Focus. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Associated Press (September 13, 1938). "Hitler's Speech Relieves America of War Fears". Fort Myers News-Press. LIV (299). Newspapers.com: 1. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ McCullough, David: Truman. Simon and Schuster, New York, New York. 1992. P. 214

- ^ "Wedding Announcement: James Hamilton Lewis and Rose Lawton Douglas". The Constitution. Atlanta, GA. November 30, 1896. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brave Companions: Portraits in History, p. 230.

- ^ "Hon. James Hamilton Lewis", p. 376.

- ^ The Senate, 1789-1989, p. 470.

- ^ Claude G. Bowers, My Life: The Memoirs of Claude Bowers, p.72 (New York: Simon & Schuster 1962) (retrieved Jul.21, 2024) ("His was almost a freak mind. Men smiled at his foppishness and his vanity, but no one doubted his ability.").

- ^ Historian of the United States Senate. "Biography, James Hamilton Lewis". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Washington, DC: United States Senate. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

Sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Byrd, Robert C. (1988). The Senate, 1789–1989: Addresses on the History of the United States Senate. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- McCullough, David (1992). Brave Companions: Portraits in History. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-79276-3.

- U.S. Senate (1939). James Hamilton Lewis, Late a Senator from Illinois. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Lewis, James Hamilton (1913). The Two Great Republics Rome and the United States. Chicago, IL: The Rand-McNally Press.

Magazines

[edit]- George, Charles E. (October 1, 1915). "Hon. James Hamilton Lewis". The Lawyer & Banker and Southern Bench & Bar Review. New Orleans, LA: Lawyers and Bankers Company.

External links

[edit]- 1863 births

- 1939 deaths

- 20th-century American legislators

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Washington (state)

- Democratic Party United States senators from Illinois

- Illinois Democrats

- Politicians from Augusta, Georgia

- Politicians from Danville, Virginia

- Candidates in the 1912 United States presidential election

- Members of the Washington Territorial Legislature

- Georgia (U.S. state) lawyers

- Washington (state) lawyers

- Washington National Guard personnel

- 20th-century Washington (state) politicians